Zika and the Brain: A Public Health Game Changer

Human infection with Zika virus (ZIKV) was initially reported to be mild and non-life threatening. However, as ZIKV has been introduced into unexposed and highly dense populations, it has evolved. We know now that when the virus attacks the brain of an unborn child, the effects can be devastating.

ZIKV can be passed from mother to fetus (in-utero) during pregnancy, which can result in microcephaly, a very serious condition resulting in life-long disabilities, and other birth defects. Today, I want to discuss ZIKV-related microcephaly and show how the number of U.S. birth defects due to possible Zika infection has alarmingly increased, leading to a serious public health concern in the U.S. and its territories.

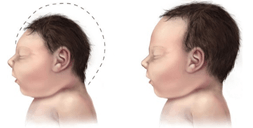

What is Microcephaly? Infections in the brain can reduce the number of cells that form during fetal brain development; resulting in a smaller head (Figure 1). This condition is called microcephaly [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates the cost of caring for a single child with microcephaly in the U.S. to be around $10 million [2]. Although this cost is astounding, it does not account for the impact on the family, nor the life-long suffering of the child.

Microcephaly Projections. The recent WHO Zika situation report suggests no evidence that the Zika outbreak is declining [3]. Furthermore, the number of travel-associated cases has increased in the U.S., and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have reported 43 cases of local transmission in Florida [4]. As more people are exposed to ZIKV, there is a strong possibility that more cases of microcephaly will be reported in the coming months.

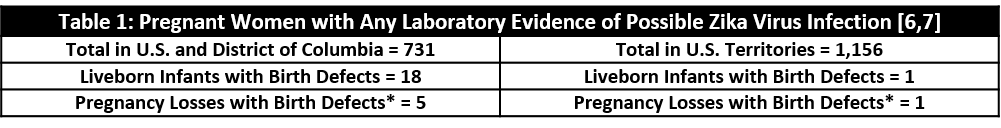

According to the U.S. National Birth Defects Prevention Network, between 2006 and 2010, microcephaly was rare—presented in only 2-12 babies for every 10,000 livebirths [5] . While there is no data yet on the exact number of infants born with microcephaly due to ZIKV in the U.S., the CDC does track the number of infants born with any birth defect (including microcephaly) to mothers who have laboratory evidence of possible Zika infection. Table 1 shows this information as of September 8, 2016 [6,7].

The situation in Puerto Rico is especially concerning. There are a total of 15,600 ZIKV cases that have been reported in Puerto Rico, with 99% of cases being the result of local transmission. According to the CDC, if the current trend continues in Puerto Rico, 25% of the 3.5 million residents will have been exposed to ZIKV [8].

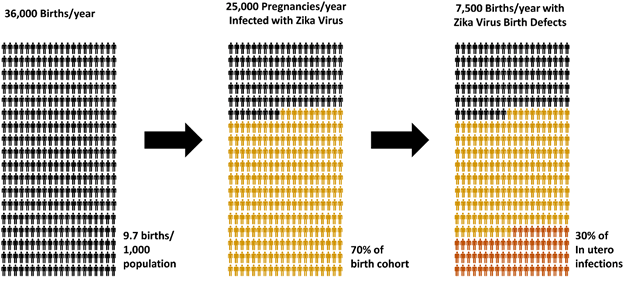

While the number of reported cases of birth defects in Puerto Rico is currently very low, there is serious concern that more cases will be seen. A recent paper published by Klase et al. projects the impact of maternal ZIKV infection on babies to be born in Puerto Rico from 2017-2018. Based on their projection, out of the 36,000 births expected during this one-year period, there will be 25,000 pregnancies where the mother is infected with ZIKV (Figure 2). Although the rate of birth defects associated with ZIKV infection during pregnancy is not currently determined, it is estimated that it may exceed 30% in some areas. These predictions suggest that approximately 7,500 births may experience ZIKV-related birth defects [9].

However, this prediction needs to be taken cautiously as the model was created using epidemiological data from multiple sources, including Brazil, and there might be confounding factors that still need to be studied. Even if the rate of birth defects associated with ZIKV infection during pregnancy was only 10%, this would still result in approximately 2,500 babies being born with birth defects in Puerto Rico.

Author: Dr. Rashid Chotani, Senior Scientist

References:

[1] CDC. Birth Defects. Facts about Microcephaly. http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/birthdefects/images/microcephaly-comparison-500px.jpg [Cited 09.11.2016]

[2] WHO. One year into the Zika outbreak: how an obscure disease became a global health emergency. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/emergencies/zika-virus/articles/one-year-outbreak/en/ [Cited 09.11.2016]

[3] WHO. Situation Report Zika Virus. 7 September 2016. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/250049/1/zikasitrep8Sep16-eng.pdf?ua=1 [Cited 09.11.2016]

[4] CDC. Zika Virus Cases in the US. https://www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/united-states.html [Cited 09.11.2016]

[5] National Birth Defects Prevention Network. Major birth defects data from population-based birth defects surveillance programs in the United States, 2006-2010. Birth Defects Research (Part A): Clinical and Molecular Teratology. 2013;97:S1-S172.

[6] CDC. Pregnant Women with Any Laboratory Evidence of Possible Zika Virus Infection in the United States and Territories, 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/pregwomen-uscases.html [Cited 09.11.2016]

[7] CDC. Outcomes of Pregnancies with Laboratory Evidence of Possible Zika Virus Infection in the United States, 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/pregnancy-outcomes.html [Cited 09.11.2016]

[8] Zika Virus. Pregnancy. Zika & Pregnancy in Puerto Rico. http://www.cdc.gov/zika/pregnancy/index.html [Cited 09.11.2016]

[9] Klase ZA, Khakhina S, Schneider ADB, Callahan MV, Glasspool-Malone J, Malone R (2016) Zika Fetal Neuropathogenesis: Etiology of a Viral Syndrome. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10(8): e0004877. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004877

[10] Cauchemez S, Besnard M, Bompard P, et al. Association between Zika virus and microcephaly in French Polynesia, 2013-15: a retrospective study. Lancet 2016 March 15

[11] Petersen EE, Staples JE, Meaney-Delman D, et al. Interim guidelines for pregnant women during a Zika virus outbreak — United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:30-3