Long-Time IEM Advisor Reflects on His Life in a New Book

Gary McConnell has been a key IEM advisor since 2003, providing a wealth of insight and wisdom based on his many years of experience as the director of the Georgia Emergency Management Agency. But the origin of his wisdom, and the formation of his character go back to his early life growing up in Chattooga County, Georgia. There he was a sheriff and the son of a sheriff, as he describes poignantly in an autobiography he just published, It’s All About The People.

The story starts with his father, a farmer whose family roots in the county go back to the early 1800s. In 1964 he was elected county sheriff but died suddenly and tragically at the age of 53. His son, Gary, only 22, was selected to finish his term and was elected sheriff himself in 1967. He was the youngest sheriff in state history when he started and served as sheriff for 20 years.

He attributes his success, after being thrust into the role of sheriff at such a young age, to the simple virtues of hard work, respect for others and sense of service to others that he learned from his father. Following those virtues, he quickly turned Chattooga County into one of the best law enforcement units in northwest Georgia according to his peers.

Sheriff Days: Moonshiners and Bootleggers

Like his father before him, McConnell campaigned on cleaning up the county’s vices. Chief among them in that dry county was moonshiners and bootleggers. He recounts that the woods were full of stills. He had a deputy who was a veritable blood hound at locating them down trails. He and his deputies would bust them up using axes. Then they would come back weeks later just to find the ax holes patched and the stills back in business. That’s when they started using dynamite.

True to the title of his book, McConnell treated the moonshiners as people. “While we were destroying stills and confiscating white whiskey, we tried to treat everyone with respect. These were basically good people doing something illegal to make a living during hard times.” He added that bootleggers would regularly invite him to have dinner with them before going to jail. “They weren’t trying to bribe you. It was just their way of saying, ‘You’re just doing your job and we’re not mad at you.’” In that manner, you might say he pioneered the concept of community policing.

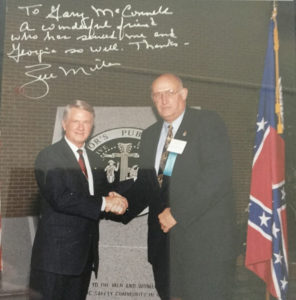

McConnell was keenly aware of the importance of human connections and being able to put a face with a name when cooperation among jurisdictions was needed. During this period, McConnell served as president of the Georgia Sheriffs’ Association and the Georgia County Officers’ Association. Making those connections also helped him become a valued campaigner for his longtime friend from northwest Georgia, Zell Miller. When Miller ran for governor in 1990, McConnell traveled the state with him as a member of his campaign staff.

On to the Georgia Emergency Management Agency

When the campaign was over, Miller asked him to join his administration and appointed him director of the Georgia Emergency Management Agency (GEMA). When he arrived, GEMA had not had a presidentially-declared disaster in more than 17 years. It was housed in the basement of a National Guard building, and while he recalls that it was a good organization, compared to the modern law enforcement practices he had introduced back in Chattooga County, it was outdated.

He rolled up his sleeves and hired more personnel and got them the best training available. He set up modern communications equipment and procedures. He also used his networking from the Sheriffs’ Association and the Georgia County Officers’ Association to establish channels of direct communication with emergency managers around the state. He usually already knew two or three emergency officials in every county, so he did not have to go through the process of earning the locals’ trust. Finally, he established up-to-date emergence response procedures that his staff learned backwards and forwards.

He made these changes just in time. The lull in disasters the state had enjoyed ended. In the 1990s, he and his staff found themselves dealing with a new disaster every six months on average. They included natural disasters such as floods, tornadoes, and ice storms. They also included man-made disasters such as marches and racial demonstrations. His boss and friend, Zell Miller, tirelessly traveled the state with him when disaster struck so that the governor could see it firsthand and get McConnell’s advice immediately.

McConnell learned that each form of disaster had its own characteristics, and each community a disaster occurred in had its own characteristics, too. So, McConnell became skilled in tailoring the response to the needs of the community. He worked closely with local emergency officials and deferred to their judgement on matters concerning the community when they knew better. These communities ranged from small towns with a single official who was also the mayor to large municipalities with a staff of well-trained emergency personnel.

He also took on the mission of increasing school safety around the state. This was well before the Columbine High School mass shooting, and it further strengthened his rapport with emergency response officials around the state. In fact, both the State of Utah and Washington, D.C. modeled their school safety program’s after what he did in Georgia.

The Centennial Olympic Park Bombing

McConnell was placed in charge of security for the state at the 1996 Summer Olympics. His job was to coordinate 29 state agencies, nearly 5,000 sworn law enforcement officers, and 25,000 civilian employees. On July 27, a domestic terrorist, Eric Rudolph, planted a bomb in Centennial Olympic Park while it was crowded with thousands of spectators who had gathered for a nighttime concert featuring a popular rock band. The blast killed 1 person and injured 111 others; another person later died of a heart attack.

This was a disaster to put any emergency response team to the test. In addition to the human tragedy, McConnell and his team had to deal with the more than 250 news people who were in the park at the time and saw everything. Fortunately, he had always maintained a good rapport with CNN and the Atlanta area news stations. Just as with the moonshiners and bootleggers back in Chattooga County, there was no antagonism, just mutual respect. Each party had a job to do.

“I was honest with them,” he recalled. “I told them everything I could, and when I couldn’t, I was straight with them in telling them why.” Only two officials in Georgia were authorized to talk to the news media, McConnell and Gov. Miller. “The members of the news media were all supportive and understanding, including the foreign press.”

After the event, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) used McConnell in their training videos, many of which are still in use today, to share his lessons learned. Of special interest to DOJ was the fact that the event included one of the earliest uses of a secondary device in which a bomber follows the initial detonation with secondary detonations timed to kill emergency responders as they arrive on the scene. In addition, the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University performed an in-depth study of the incident, and McConnell was one of 25 people researchers interviewed intensely.

As the State of Utah was preparing for the 2000 Olympic Games, McConnell was again tapped to provide expert advice. He was also invited to speak at emergency management conferences around the world for years afterward. The theme of his remarks always came back to his belief that, while advances in procedures and technology are great, emergency response and disaster management is, at its heart, a people business first.

Joining IEM

McConnell was aware of IEM’s presence at emergency management conferences over the years and knew IEM had a good reputation in the industry for the ethics and competence of its people. Upon leaving GEMA after running it for 12 years under two governors, a couple of his friends at DOJ recommended that he meet IEM founder and CEO, Madhu Beriwal. Upon meeting, they both saw that McConnell was a good fit for IEM in the role of senior advisor, and Beriwal wasted no time in hiring him.

At IEM, he has had a major role in disaster planning for federal agencies and states around the nation. He has also provided guidance on some of IEM’s largest disaster recovery projects, including recovery from Louisiana’s severe flooding in 2016. His work in hurricane preparation for IEM customers has resulted in improvements to state and county search and rescue procedures and evacuation protocols. Also, his years of friendship with emergency managers across the nation has been very helpful to IEM’s business development efforts.

Looking Forward, Looking Back

As McConnell looks ahead, he sees two major trends. The first is that the weather has definitely changed over the past 20 years and continues to change. Storms are more frequent and intense. Second, he sees the technology for managing disasters ever improving. “Technology is great, integrate it with the training, the resources available, and the staff. But never lose touch with the fact that it’s about real people. All those symbols on a computer screen are people.”

Looking back, he sees that the values he has carried with him his whole life are still essential to the mission of emergency management and disaster response—hard work, respect for other people, and a commitment to taking care of those in need.