A Conversation with Bryan Koon on Disaster-Related Costs, Preparation and Resilience

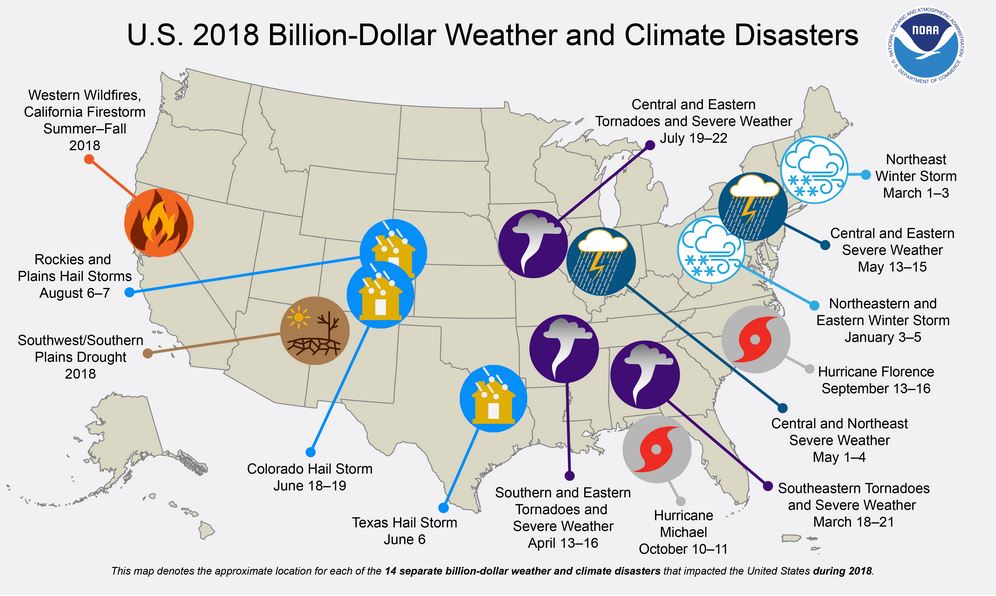

At the start of each new year, the National Centers for Environmental Information at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) releases a report on the costs of the prior year’s disasters, including hurricanes, wildfires, floods, droughts, severe local storms, and winter storms. At this time last year, NOAA announced that 2017 set a record at $312.7 billion in damages caused by 16 separate $1 billion or more disaster events. While the number for 2018 is not as high at 14 separate disasters costing at least $1 billion each and an overall damage toll of $91 billion, the trend is clear. Between 1980 and 2013, the average was six per year, and from 2013 to the present, the average has been 12.

At the start of each new year, the National Centers for Environmental Information at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) releases a report on the costs of the prior year’s disasters, including hurricanes, wildfires, floods, droughts, severe local storms, and winter storms. At this time last year, NOAA announced that 2017 set a record at $312.7 billion in damages caused by 16 separate $1 billion or more disaster events. While the number for 2018 is not as high at 14 separate disasters costing at least $1 billion each and an overall damage toll of $91 billion, the trend is clear. Between 1980 and 2013, the average was six per year, and from 2013 to the present, the average has been 12.

Helping put this trend into perspective is Bryan Koon, IEM’s Vice President of International Homeland Security and Emergency Management. From 2011 to 2017, he was the director of the Florida Division of Emergency Management. He is a much sought-after expert on emergency management, having been quoted in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg News, The Hill, and Emergency Management.

Q. Can you please describe how NOAA establishes these figures?

NOAA has data going back to 1980 and pulls together the best available data from federal agencies including FEMA, the Department of Agriculture, the Energy Information Administration, the Army Corps of Engineers, and the National Interagency Fire Center plus state agencies and private organizations such as the Insurance Services Office. The costs are derived from physical damages to buildings; damage to roads, bridges, and other infrastructure; losses to crops, livestock, and timber; damaged vehicles and boats; lost time suffered by businesses and the costs of restoration; and, in the case of wildfires, fire suppression.

Q. Who uses this information and for what?

There are some very important users of this data because it provides trends based on types of disasters, their locations, and rising and falling incidents and associated costs. The reinsurance industry, catastrophe modelers, and government agencies such as the National Hurricane Center include this information in their risk assessments so that they can better develop response plans and allocate resources.

Q. What are the most expensive disasters?

Hurricanes and tropical cyclones top the list at an average cost of $21.8 billion, once they top the $1 billion threshold to be counted in the NOAA report. After that, it is severe drought at an average of $9.7 billion each followed by flooding at $4.3 billion, wildfires at $3.7 billion, winter storms at $3.0 billion, and severe local storms at $2.2 billion.

Q. How are these disasters distributed across the nation?

For starters, each of our 50 states has experienced a disaster of $1 billion or more. Alaska has had only one since 1980; Texas has had over 100. Overall, the Central Plains and the southeastern United States are more prone to disasters than the rest of the country. Wildfires are most common in the West; droughts are most common in the Central Plains and southern states; and severe local storms most often occur in the Plains, Southeast, and Ohio River Valley. Floods occur in the parts of the nation most crisscrossed by rivers, such as along the Mississippi and the Ohio, and along the Gulf Coast. Tropical cyclones occasionally hit Hawaii, but, of course, hurricanes repeatedly hit the Gulf States, from Texas to Florida in the Gulf and the Atlantic states from Florida up through New England.

Q. Disasters seem to be getting bigger and more expensive every year. Why is that?

We have to accept the role of climate change as a factor in storm intensity. But it is not the only one. More and more people are choosing to live in disaster-prone areas such as the Gulf and Atlantic Coasts and the urban interface areas in the mountains of the West. Another problem is that when homes are destroyed, the owners tend to rebuild bigger but not necessarily better.

Q. Better?

By “better” I mean “more disaster-resistant,” like that photo of the house in Mexico Beach, Florida, that went viral on the Internet because it was the only one in its waterfront neighborhood that survived Hurricane Michael intact. Hurricane Michael demolished nearly every home and business in its path, including the Mexico Beach police station. But this house remained standing with very little damage. The owner of the house built it on top of very tall pilings so that the storm surge could flow under it. It had 1-foot-thick concrete walls as well as steel cables to hold the roof down. The windows survived almost intact because they had an outer pane, a spacer, and a stronger inner pane.

Having weathered that storm so well, the owner knows full well that the next big one is coming, so he is now adding even more improvements. He will be installing stainless steel supports and ties, and he’s replacing his front door with a hurricane door shutter.

Not everyone can afford to do all that, but it is relatively inexpensive to make substantial improvements to your home. Retrofitting a roof with trusses that have good horizontal and vertical bracing is about $1,000 for a 2,000-square-foot roof, the average size in the United States. When building a house from scratch, it could cost as little as 3 percent to 5 percent more to harden the house with stronger building materials plus fortify the roof, windows, and doors. Installing storm shutters and garage-door supports is a good idea, too. Finally, clean you gutters, prune your trees, and invest in hurricane-resistant tree species with strong root systems.

Q. How about wildfires?

Although hurricanes tend to receive the most news coverage, wildfires, both large and small, are a growing threat in the western United States and parts of the South such as Florida. You can take some simple steps to make your home less vulnerable to the threat of wildfires:

- Clear leaves and other debris from gutters, eaves, porches, and decks.

- Remove dead vegetation and other items from under your deck or porch and within 10 feet of the house.

- Prevent debris and combustible materials from accumulating under your house by screening below patios and decks with wire mesh.

- Remove stacked firewood and propane tanks from within 30 feet of your home.

- Prune trees so the lowest branches are 6 to 10 feet from the ground.

- Keep your lawn well-watered. If the grass is brown and dry, keep it cut short.

- Inspect shingles or roof tiles. Replace or repair those that are loose or missing to prevent ember penetration.

- Cover exterior attic vents with metal wire mesh to prevent sparks from entering the home.

Q. If the latest United Nations’ scientific panel on the effects of climate change by 2040 is accurate, how do you envision the relationship between human civilization and nature changing?

That’s a good question and it requires a long answer. There’s an old saying familiar to anyone involved in disaster recovery: nature always bats last. And that was certainly the message of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released last October. It was a stark warning.

It said that we can expect more extreme and rapidly forming storms, like Hurricane Michael in the Florida Panhandle last October. It also predicts extreme rainfall events that will result in catastrophic flooding, like the 30 inches of rain from Hurricane Florence that inundated North Carolina last September.

These are the kinds of catastrophes we deal with as communities with the help of the states and the federal government. On a grander scale and potentially of even greater consequence is the report’s prediction of prolonged droughts and desertification of parts of the world leading to climate-change refugees migrating to other countries. This is a phenomenon that is only going to increase, and planners in the U.S. State Department and the Pentagon are taking it seriously as a national security issue.

Q. What can ordinary citizens do to ready themselves for the kind of profound changes you describe?

For those of us doing our best to lead our day-to-day lives in the midst of these changes, there are some simple, practical things we can do. We will all need to recycle more, switch to green energy sources, and drive less—all things that reduce your carbon footprint.

We are also going to have to think long and hard about our choices of where to live. Do we really want to live right on a beach in the southeastern United States or in the foothills in a western state?

Insurance underwriters are under pressure from their reinsurers—the ultimate financial backstop in their industry—to stop writing policies for these kinds of properties. At the same time, policy makers are re-evaluating programs like the National Flood Insurance Program, questioning whether these programs create the wrong kind of incentives for homeowners by paying them to rebuild rather than relocate.

Q. How would relocating work?

Over the long-term, we as a nation are going to have to follow a policy of retreat and rebuild. We will have to retreat from the most vulnerable areas through government buyout and through market forces. And we are going to have to build better where we do live by following the kind of hurricane- and wildfire-resistant practices I already mentioned. In fact, homes without those protective features may become uninsurable as time goes on.

Finally, we are going to have to protect our public infrastructure. That means our roads and bridges, power plants, harbors, water-treatment facilities, and dams. We can reduce the risks by building in low-risk areas, but much of what has already been build is located in vulnerable areas. Where they cannot be relocated, they will have to be retrofitted, which is an expensive process that requires government direction and financing. It is currently being done by FEMA under its Hazard Mitigation Grant Program executed by the states.

Q. What kind of innovations do you see coming in disaster preparation?

A promising new area of disaster mitigation is green infrastructure. Examples are the replanting of existing wetlands and the creation of new ones to act as buffers against flood surges and sea-level rise. The State of Louisiana is proving the concept by restoring and enhancing its barrier islands and even building new ones that are planted with natural vegetation. By helping Mother Nature along, they not only receive the storm- and flood-mitigation benefits, but they also get new natural habitat that is beneficial to the state’s fishing and tourism industries. I believe that those kinds of projects that work with nature and have positive side effects have a great future as we face the new normal of climate change.